Adult, Able-bodied Unmarried Daughters Can't Claim Maintenance Now Under Section 125 CrPC: Jammu & Kashmir High Court

- Lawttorney.ai

- Apr 15, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 16, 2025

Case Title: Abdul Raheem Bhat v. Beauty Jan and Others

Introduction

The jurisprudence surrounding adult unmarried daughter maintenance has taken yet another definitive turn, with the Jammu & Kashmir High Court recently reinforcing an established legal principle. The ruling reiterates that an adult, able-bodied unmarried daughter cannot claim maintenance from her father under Section 125 CrPC (now Section 144 of BNSS), unless she is physically or mentally incapable of sustaining herself.

This judgment aligns with the decisions of several other Indian courts, including the Kerala High Court, Punjab and Haryana High Court, and the Supreme Court, which have all echoed a similar interpretation. The decision upholds the delicate balance between parental obligations and the independence expected from an adult offspring.

In this blog post, we’ll break down the ruling of the Jammu & Kashmir High Court, explore parallel judgments like the Kerala High Court’s view, and walk through landmark cases like Abhilasha v. Parkash to fully understand the evolving contours of the legal rights of daughters in the context of maintenance laws in India.

Context and Legal Framework

What is Section 125 CrPC (Now Section 144 of BNSS)?

Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) is a secular provision designed to prevent destitution and vagrancy. It mandates that a man must maintain his wife, minor children, and parents if they are unable to maintain themselves.

However, when it comes to adult daughters, the law is stringent. A daughter who has crossed the age of majority (18 years) can only claim maintenance under Section 125 CrPC if she is unable to maintain herself due to physical or mental disability. This position has been upheld across various Indian High Courts and by the Supreme Court.

Under Section 125 CrPC, the following individuals are generally not entitled to claim maintenance:

1. Minor Wife: If the wife is a minor and the marriage is declared void or annulled.

2. Self-Sufficient Wife: A wife who is earning sufficiently and can maintain herself.

3. Disobedient Wife: A wife who refuses to live with her husband without any reasonable cause or justifiable reason.

4. Adulterous Wife: A wife living in adultery is not entitled to claim maintenance.

5. Person Capable of Maintaining Themselves: Any person who is capable of maintaining themselves and does not fall under the categories of wife, child, or parents who are unable to maintain themselves.

Who can claim and get maintenance Under Section 125 of CrPC:

According to Section 125 (1), the following person can claim and get maintenance:

1. Wife from his husband,

2. Legitimate or illegitimate minor child from his father

3. Legitimate or illegitimate Minor child (Physical or Mental abnormality) from his father,

4. Father or Mother from his son or daughter

Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956

In contrast, the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act (HAMA), 1956, particularly Section 20(3), offers some relief. Under this provision, a Hindu father is obligated to maintain his unmarried daughter, irrespective of age, if she is unable to maintain herself. Still, this entitlement requires solid evidence of her inability to sustain herself due to incapacity.

Recent Case: Jammu & Kashmir High Court Ruling

In a case before the Jammu & Kashmir High Court, an adult unmarried daughter had approached the court seeking maintenance from her father. She had claimed maintenance under Section 125 CrPC, arguing that she had no independent source of income and was therefore entitled to financial support.

The High Court, however, dismissed her claim. The court reasoned that since the daughter had attained majority and failed to produce evidence of any physical or mental disability, she could not claim maintenance under Section 125. The court emphasized that financial dependence alone is not a sufficient ground for awarding maintenance once the daughter becomes an adult.

This decision is consistent with judicial precedent and highlights a critical gap in understanding the legal rights of daughters post-majority.

Kerala High Court’s Viewpoint

The Kerala High Court, in a similar judgment, had faced a situation where an unmarried major daughter claimed maintenance under Section 125 CrPC. The case was presided over by Justice A. Badharudeen, who unequivocally stated that:

"An unmarried daughter who has attained majority is not entitled to maintenance under Section 125 CrPC unless she is able to prove that she suffers from a physical or mental abnormality or injury that prevents her from maintaining herself."

Background of the Kerala Case

The petitioner, the father of the daughter, had filed a revision petition challenging the family court’s decision to grant maintenance. The daughter, having attained majority, had claimed maintenance solely on the grounds of being unemployed and dependent.

However, the Kerala High Court observed that financial dependence alone cannot justify a maintenance claim under Section 125 CrPC once the individual has become an adult. The daughter did not submit any evidence of physical or mental challenges that would hinder her ability to sustain herself. As a result, the court overturned the family court's order.

This judgment reaffirmed the doctrine that adult unmarried daughter maintenance under Section 125 CrPC is not absolute and is subject to strict conditions.

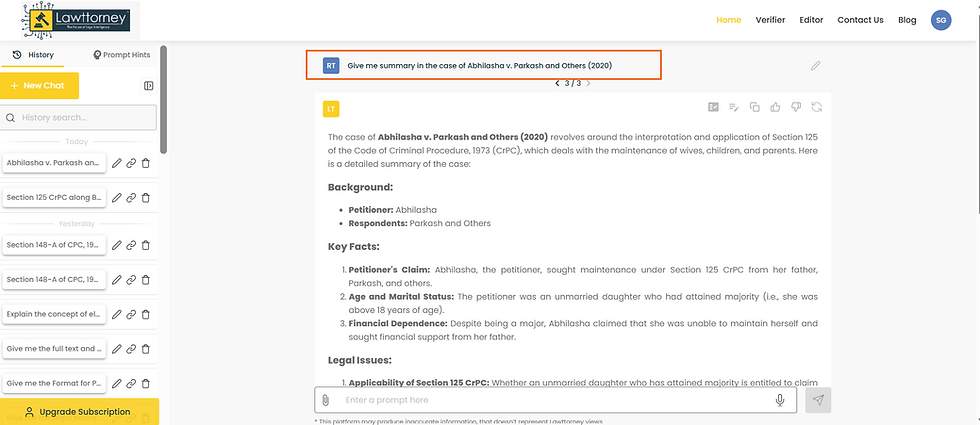

Supreme Court Verdict: Abhilasha v. Parkash (2020)

The Supreme Court of India addressed this issue definitively in the landmark judgment of Abhilasha v. Parkash and Others (2020). The facts of the case trace a long judicial journey, starting from a family court and culminating in the apex court.

Chronology of Legal Proceedings:

Judicial Magistrate's Ruling (2011): The matter was filed u/s 125 of CrPC. Abhilasha’s mother filed an application for maintenance for herself and her three children, including Abhilasha. The learned Judicial Magistrate dismissed the application under Section 125, holding that the court had granted maintenance only until Abhilasha attained majority.

Sessions Court (2014): The decision was upheld, and the timeline for maintenance was reiterated to end at Abhilasha’s attainment of majority in 2005.

Punjab and Haryana High Court (2018): The High Court dismissed Abhilasha’s application filed under Section 482 CrPC, stating that she is not entitled to maintenance post-majority unless proven physically or mentally incapable.

Supreme Court (2020): The Supreme Court also dismissed her appeal, reinforcing that under Section 125 CrPC, maintenance is not claimable by an adult daughter unless there is an incapacity.

However, the court also noted that if Abhilasha had approached the court under Section 20 of the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, she might have had a better case. But since her petition was under Section 125 CrPC, her claim was legally untenable.

Legal Position Summarized

The consistent pattern in these judgments is as follows:

Law | Claim Possible by Adult Daughter? | Conditions |

Section 125 CrPC | No | Unless she proves physical/mental incapacity |

Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act (Section 20) | Yes | If she is unable to maintain herself |

General Dependency (Unemployed, Unmarried) | No | Not a valid ground under Section 125 |

Why This Matters: Implications for Indian Families

This judicial clarity has major implications for family disputes involving maintenance. It offers fathers legal recourse to deny claims where there is no disability or legitimate inability to earn.

However, this also presents a challenge for young adult women who may still be pursuing higher education or struggling to enter the workforce. The law essentially draws a hard line: if you are an adult and not disabled, you are expected to earn your keep.

This places the burden on daughters to prove their incapacity, not merely their financial distress. This legal nuance must be understood clearly by those seeking maintenance under Indian laws.

Criticism and Counterpoints

While these rulings make legal sense, some critics argue that they may not be entirely just from a social perspective. In many parts of India, especially rural and conservative areas, women—even after turning 18—do not have access to jobs or higher education due to social norms.

Also, in several cases, daughters may be dependent on their fathers due to family circumstances beyond their control. Yet, the rigid interpretation of Section 125 CrPC offers them no remedy unless they go through the more complex route of filing under HAMA, 1956.

Conclusion

The legal stance taken by the Jammu & Kashmir High Court, Kerala High Court, and Supreme Court reflects a strict and consistent interpretation of the law. An adult unmarried daughter's maintenance claim under Section 125 CrPC will not succeed unless she can prove she is physically or mentally incapable of self-support.

For such claims, the better legal route would be under the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, where the scope is broader but also more demanding in terms of evidence.

For parents and daughters alike, it is essential to understand these nuances and approach the courts with the correct legal framework. The legal rights of daughters are protected, but within clearly defined boundaries of capacity, age, and dependency.

Final Word

The responsibility of parents ends, in most legal contexts, once their child attains adulthood—unless there is a specific reason requiring extended support. The Indian legal system, through various landmark rulings, has set the boundaries on adult unmarried daughter maintenance, reinforcing the importance of self-sufficiency in adulthood unless proven otherwise.

As societal norms continue to evolve, there might be future amendments or judicial interpretations to soften this stance. Until then, clarity in legal strategies and awareness about available legal options remains paramount.

Empower Your Legal Practice with AI – Join Our Free Webinar!

Are you a legal professional looking to boost your efficiency and stay ahead in a competitive field? Discover the power of Lawttorney.AI – the cutting-edge tool designed to streamline legal research, automate tasks, and enhance productivity.

👉 Don't miss out! Reserve your spot in our FREE webinar and experience the future of legal practice today. Register Now

Comments